The Last Bite Club

Make every bite count.

Don’t like reading? Allow me to read it to you 👈

Is this the last sentence?

No, that was the first and this is the second. Like lemmings emerging en masse from a faraway sphagnum bog, sentences follow each other to the cliff edge of your brain and hurl their bodies into the void. May I take your order?

Order is important. We eat each sentence, first-first, and last-last, spitting punctuation bones into a bowl of understanding. Or misunderstanding, depending on the day. Middle sentences patiently mediate between hot-right-out-of-the-box openers and shut-it-down closers—not an easy task when both think they are the star of perfect prose.

“I am the most delicious!”

“No, I am the best bite!”

May I interest you in a tangent paragraph? Believe me, it will wind around several tables, through the kitchen, and out into the back alley for a smoke before bringing you back to The Point’s table.

As children, my brother and I were not allowed to leave the table until we ate everything on our plate. I say this with no recollection of the consequences should we not eat everything, but saying something like “No TV!” would’ve made me eat the plate when I was little, so perhaps that? There was no point arguing—it was just accepted that you had to eat it all—and as a result, I developed a very specific and methodical way of eating which I still practice to this day (minus the clean plate part.)

I save my favorite thing for last.

Yes, I am a ‘last bite is the best bite’ person.

The last bite is the high note. The joy note. The firework finale to set me off with a bang.

But…hmmm.

Is the last bite/best bite an approach that can be applied to writing? Isn’t it mighty risky to hang so much weight on the last sentence or paragraph? Well, duh. Yes. That approach relies on the reader getting to the last line in the first place and by doing that, you sure are putting a lot of faith in things (aka humans) that perhaps don’t deserve that faith. After all, attention spans are on high scroll, first-few-seconds-and-out mode these days. Last bites in writing matter—this is not new—but know that they can’t be the only special on the menu. All sentences matter.

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.”

To put it mildly, that’s a good first line. It hits the tongue with an instant burst of flavor that gets the ghrelin gurgling in the tum-tum cave. “More,” you say. “I want more and there ain’t no ‘please, Sir’ about it.” And you get more. A whole lot more sustenance and bitterness and bad tastes and phrases that burn the back of your throat and all the way down. ALL. THE. WAY. DOWN.

And then…

“He loved Big Brother.”

A last line, waving sinister back to the first1. Both are bangers, of course. Crafted and constructed as carefully as I construct my best last bite, but a good first and last—is that all you need to win dinner? One zesty appetizer finished with a deliciously cruel dessert?

Luckily for us, Orwell was a Master Chef and hung those two tasty morsels together with his god-like gravy and now, well…, now I guess we live in his vision. But that’s a story for another day. Point is, he wrote the whole meal using all the ingredients available to him in his kitchen. A multi-course feast with juicy paragraphs, and endless rounds of delicious and decadent tastes to assuage our gluttonous leanings and stuff us to bursting. We gorge ourselves to the “bring me a bucket” precipice of it. He knows a good first or last line cannot exist without the peas and carrots of it. The grease in between.

The best thing about books and stories is committing yourself to the dining experience. Of knowing you’re destined to eat everything on the plate, both pleasant and unpleasant, and digesting it all at a leisurely pace. Uncomfortable subjects that still taste divine. Rich flavors and textures that course through the blood to stop a heart. Sweet, sour, salty, bitter—it doesn’t matter. Reaction is the Sheriff of Flavor Town2 and you should consider yourself deputized.

Was there a point to all this? Am I just trying to get to the last sentence so I can go and make coffee? Probably, but know that I’ll keep on coming back to noodle in my test kitchen, taste testing as I go, and setting off smoke detectors with my burned-bottomed pans. I’ll keep doing that until I’ve cooked something that’s worth eating. Because it doesn’t matter if you’re asking someone to call you Ishmael3, or farewelling from your little droog4, you’ve simply got to lay your table and serve a purpose. Taste, flavor, exposition, nutrition. Roast ‘em all and cross your fingers that when someone gets to the last line they are satisfied enough to close the chapter with a mighty burp5.

And this is my last sentence.

Yours in tiny thought,

Janeen

This week’s amends…

“I believe that each of us is given one sentence at birth, and we spend the rest of our life trying to read that sentence and make sense of it. We write hundreds of poems, and many books and paragraphs and lines, in order to understand that one sentence.”- Li-Young Lee

So much good stuff in this interview from 1995.

Via Malaka’s List of Beautiful Things

On Rotation: “Our Anniversary” by Smog.

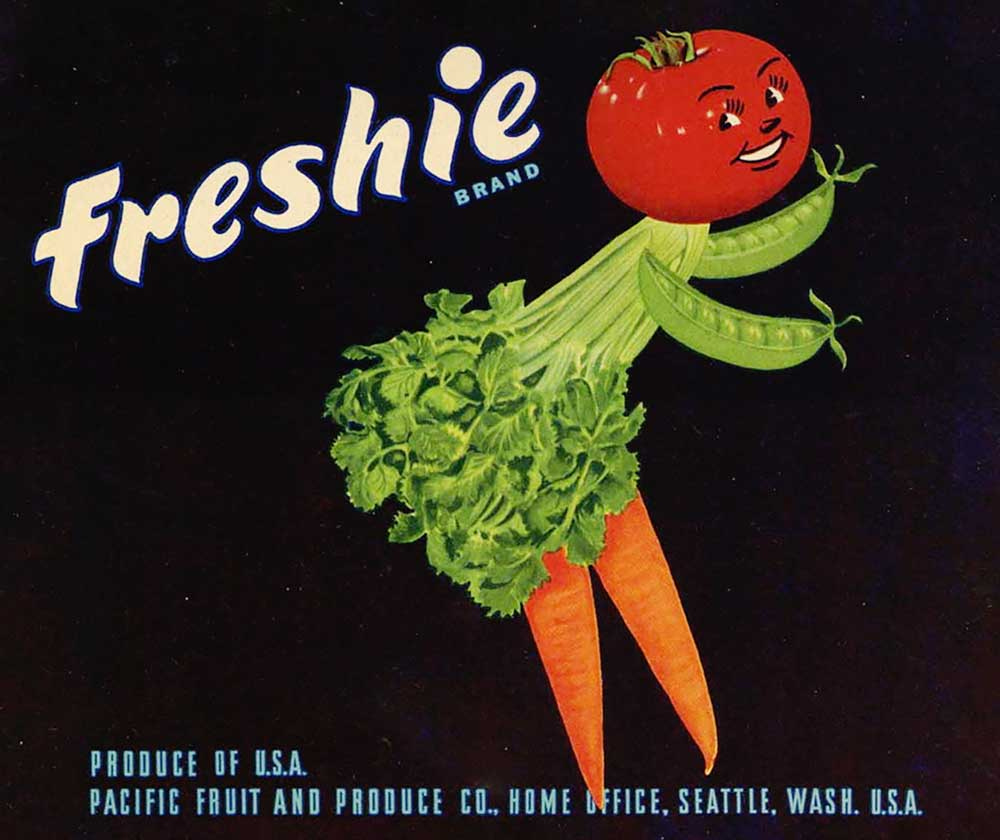

These produce labels from the 1880s to 1950s are lovely. See more of these beauties, here.

“In many ways, produce crate labels can be considered a byproduct of the US rail system, as the explosion of cross-country train routes in the late 1800s led to an increased availability of mass-merchandized foods, which in turn birthed the concept of branding produce for consumer appeal.”

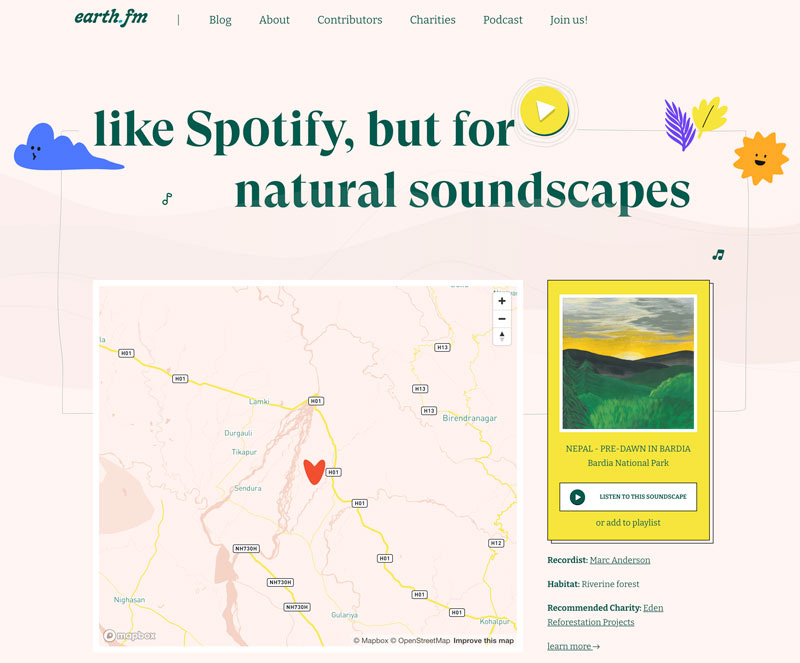

“We’re building a non-profit, free repository of pure, immersive natural soundscapes as a fundraising platform for local, grassroots charities that support the restoration of our natural world.”

Via Messy Nessy’s 13 Things

1984.

"And so farewell from your little droog. And to all others in this story profound shooms of lip-music brrrrr. And they can kiss my sharries. But you, O my brothers, remember sometimes thy little Alex that was. Amen. And all that call.”

Last lines (or are they?) from A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess. The American version of this book prior to 1986 is different, with the final redeeming chapter—Chapter 21—omitted. I believe Chapter 20 ends on the line: “I was cured all right.”

I burped after this one, but Cormac quite often makes my stomach fizz with delight. This is the last page of All the Pretty Horses.